Often commended as “the last great newspaper comic,” Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes garnered immense success and an enduring legacy over its impressive ten-year run (1985-95). By turns playful, dark, poignant, and witty, the comic strip offered broad scope as it followed the adventures of the precocious yet immature Calvin and the more sardonic Hobbes — a stuffed tiger that appears anthropomorphized and alive only to Calvin. The narrative heart of Calvin and Hobbes lies in the oftentimes unlikely friendship shared by the titular characters, but its intellectual subtexts elevate the work above other comic strips.Since its publication, Calvin and Hobbes has been singled out for its philosophical preoccupations. The ethics and values of the strip have resulted in a slew of academic analyses. At a base level, this is apparent through the names that Watterson chose for his protagonists. Calvin derives from the theocratic reformer Jean Calvin, while Hobbes takes his moniker from the empiricist philosopher Thomas Hobbes. The inherent dichotomy between these two dialecticians was explored through Calvin and Hobbes’ interactions with one another during the comic strip’s run, presenting disparate worldviews. However, Calvin and Hobbes is special in that Watterson never allowed this potentially pretentious narrative conceit to undermine the comic’s charming characters and humor.Watterson’s distaste for Calvinist philosophy is evident, given he presents a six-year-old child as its mouthpiece. Calvin’s make-believe is often imbued with a latent desire for authority and material gain underpinned by a dismissal of women, as seen through his excluding and bullying behavior towards Susie Derkins. While playing with Hobbes, Calvin expresses an inclination towards notions of fate and predetermination, to which Hobbes exclaims, “What a scary idea!” Appearing early in Calvin and Hobbes’ run, this moment was one of the first to intimate philosophical disharmony between the title characters. Coupled with the implications of Calvin’s avenues of play, the character ultimately aligns himself with Calvinist thought.RELATED: A Complete Guide to Reading Calvin and HobbesRELATED: Calvin and Hobbes Debate Exactly How Santa Claus Defines the Term ‘Good’

Often commended as “the last great newspaper comic,” Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes garnered immense success and an enduring legacy over its impressive ten-year run (1985-95). By turns playful, dark, poignant, and witty, the comic strip offered broad scope as it followed the adventures of the precocious yet immature Calvin and the more sardonic Hobbes — a stuffed tiger that appears anthropomorphized and alive only to Calvin. The narrative heart of Calvin and Hobbes lies in the oftentimes unlikely friendship shared by the titular characters, but its intellectual subtexts elevate the work above other comic strips.

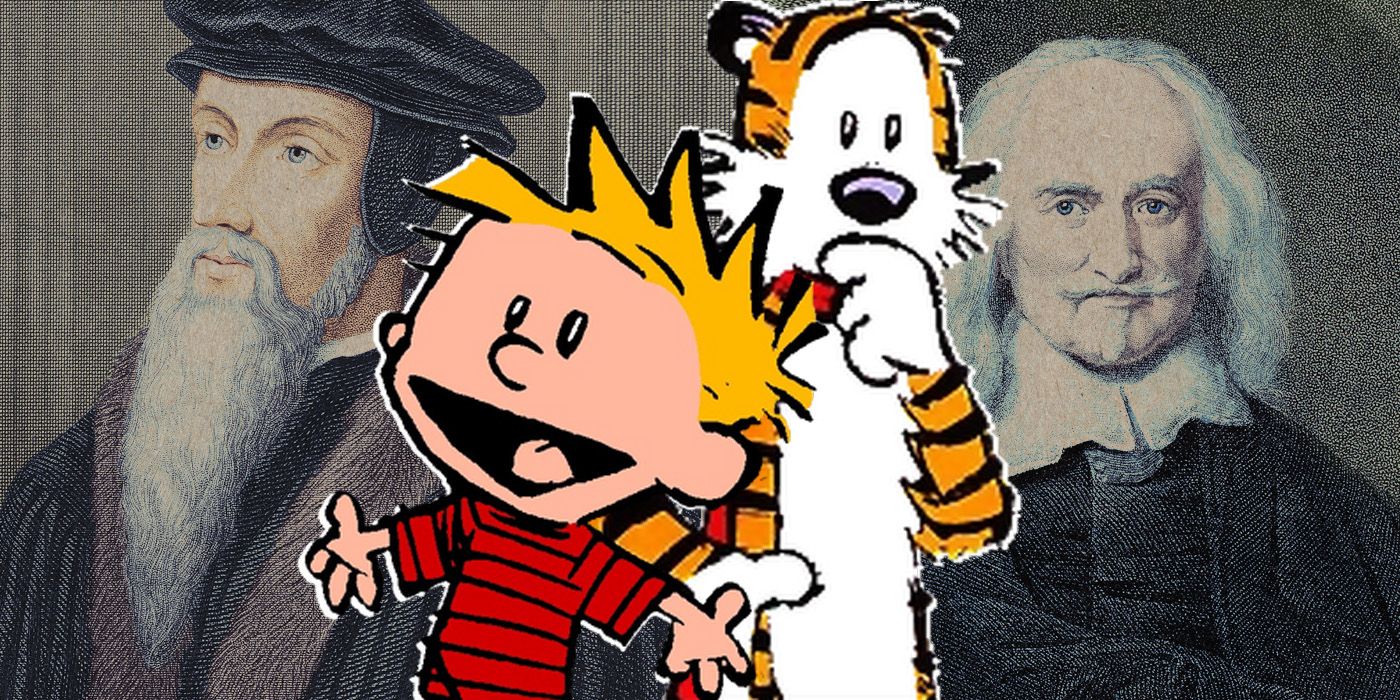

Since its publication, Calvin and Hobbes has been singled out for its philosophical preoccupations. The ethics and values of the strip have resulted in a slew of academic analyses. At a base level, this is apparent through the names that Watterson chose for his protagonists. Calvin derives from the theocratic reformer Jean Calvin, while Hobbes takes his moniker from the empiricist philosopher Thomas Hobbes. The inherent dichotomy between these two dialecticians was explored through Calvin and Hobbes’ interactions with one another during the comic strip’s run, presenting disparate worldviews. However, Calvin and Hobbes is special in that Watterson never allowed this potentially pretentious narrative conceit to undermine the comic’s charming characters and humor.

Watterson’s distaste for Calvinist philosophy is evident, given he presents a six-year-old child as its mouthpiece. Calvin’s make-believe is often imbued with a latent desire for authority and material gain underpinned by a dismissal of women, as seen through his excluding and bullying behavior towards Susie Derkins. While playing with Hobbes, Calvin expresses an inclination towards notions of fate and predetermination, to which Hobbes exclaims, “What a scary idea!” Appearing early in Calvin and Hobbes’ run, this moment was one of the first to intimate philosophical disharmony between the title characters. Coupled with the implications of Calvin’s avenues of play, the character ultimately aligns himself with Calvinist thought.

#Named #Calvin #Hobbes

Note:- (Not all news on the site expresses the point of view of the site, but we transmit this news automatically and translate it through programmatic technology on the site and not from a human editor. The content is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.))